Your Past Beliefs Are Still Running The Show

December 02, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

How much does your upbringing still shape you? Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff explore how childhood worldviews, even those you barely remember, set the foundation for your decisions and relationships. Learn why combining old perspectives with new insights helps entrepreneurs understand themselves, connect with others, and identify opportunities in a world that keeps on changing.

Show Notes:

The beliefs you formed as a child still shape how you approach life and business today.

Kids once had the freedom to explore, play, and learn without constant supervision.

School is often a miniature version of society, full of social experiments and life lessons.

Asking older generations about their youth is a great way to deepen connection and spark fresh insight.

History reminds us that opportunities and limitations were shaped by things like gender and culture.

The strongest relationships fill gaps in our lives, giving us things we needed but didn’t have.

A narrow worldview can make it hard to accept new ideas or be open to others.

Everyone wants to feel seen, valued, and understood.

Parents often struggle with self-reflection because busy lives leave little room for introspection.

Resources:

Learn about Strategic Coach®

Learn about Jeffrey Madoff

Casting Not Hiring by Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff

Who Not How by Dan Sullivan with Dr. Benjamin Hardy

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: We never know where we're going to start, we never know where it's going, and we never know how it's gonna end. But we got on to talking about our early life experiences in the 1940s. I was born in ‘44, Jeff was born in ‘49, and we were talking about school experiences, grade school, junior high, and high school, and what our experience has been over the years, largely through reunions, high school reunions especially, and we were just talking about that. But I was in a very small generation, so I was born in 1944, and so during the Depression in the 30s and during the Second World War, the population was lower, and then within a year after the end of the Second World War, all of a sudden, the baby boom started, and Jeff is a Boomer, and I'm part of what is called The Silent Generation. You just took advantage of the fact that they had built up for much bigger populations than we did.

So when I went to school, there was a lot of time with the teachers. When I got into the job market, you could get a job very, very easily, and not so for the Boomers. The Boomers had a very competitive generation. There's overflow in all the institutions of life and all the situations of life. There was just a lot of people. It's interesting to think about that. And I was mentioning to Jeff about a professor I read a long time ago, and he had a view, you know, kind of a thesis of his that when you're about 10 years old, whatever is going on in the world at that time has a big impact on you. So I was born in ’44. In 1954 I was 10 years old and Eisenhower was the president, war hero, and not a particularly political person from the standpoint of Republican or Democrat. It was just, it was Ike. Everybody liked Ike, and that was it. But I had a sense of enormous abundance. The United States was just really, really flying economically. Politically, it wasn't too polarized, and it was a different world that I was born into.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you had said that Massey spoke about one's worldview being formed by the time they were 10 years old. And for myself, that's not the case. Because, you know, the different things that I was concerned with at different times of my life, and what became kind of the benchmark when I was a kid, you know, I have two kids of my own now that are 31. A very good comedian, Nate Bargatze—I'll give him credit for this because he's very good. And he was, I think, 46 or 47. He said, I have more in common with the Pilgrims than I do with my own kids. You know, they grew up with cell phones and iPads. And my kids were the first ones that kind of grew up with computers. Like, I was one of the first generations that grew up with television for the first time. You know, that came into your life early, but not as early as it did into mine. I grew up with radio. And we, I don't remember sitting around listening to radio, but we did watch TV. And when color TV came out, my dad was the first person in the neighborhood to buy a color TV. I remember seeing Peacock.

Dan Sullivan: It was great.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it was quite fascinating. And my perception of the world at that time, I was 10 in 1959. I don't even know if I knew what a worldview was. I don't know if I had much of one. Because, you know, what you know is what you know. And when you're a kid, what you're familiar with, I mean, that's sort of the world that you know. But one of the things that I was aware of and has carried me through to my current time is, and this is probably a result of being Baby Boomers, is our neighborhood, there are probably 14 kids in these two blocks that you go outside, there's somebody to play with. And you just went out and you played. And you knew that you had to get home for dinner. But did my parents know where I was? No. Was there a cell phone to call me? No. Was there any of that? No. And the surprising thing is, no surveillance.

Dan Sullivan: No surveillance.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. You know, no surveillance unless you lived in a neighborhood that had somebody that kept track of everybody and they didn't have kids, which was kind of interesting. That's right. It was just truly, let's go out and play. And then whatever that turned into, whether it was a ball game or playing an army or whatever the hell it was, you know, it was that. And as I got older and became more aware of a greater world around me, which was probably the most significant thing was twofold. One, being in athletics, you know, I was on the wrestling team. So going to very different cities and very different economic groups. Like my high school, I was part of the third graduating class. It was a new and very good high school and it was, solidly, for the most part, middle and upper middle class. And, you know, when you're in sports, you go into areas that you only heard about, you know, because the world wasn't that integrated at that time. And it was exposed me to things that, and my dad did, but exposed me to things that I didn't know about before.

Well, it wasn't until college that my worldview changed substantially. And when we think about when we graduated from high school, the world we knew up to that time, which I think was pretty cocooned, certainly in my lifetime, it was quite cocooned. And then you, in my case, left high school in 1967. And Martin Luther King was assassinated in ‘68. Bobby Kennedy was assassinated. The cities were burning. Vietnam War was tearing the country apart. There was so much turmoil, none of which I was really aware of when I was younger. And one of the neat things about the high school reunion was, like you, you went through schooling, a lot of the kids from kindergarten all the way through 12th grade till you graduated. You know, we were talking before we started recording about how, you know, it's really interesting. It's like a petri dish of society. You know, all that melding. There was a wide spectrum of people that I went to high school with. Not that wide, considering other parts of Akron, and not nearly as wide as it would be after I left Akron, but it was from a very cocooned place out into a world that was a lot more chaotic than the one I grew up in, felt like, anyhow.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, we lived as the crow flies. I was probably 70, 80 miles to the Northwest from, that's where I grew up. And it was industrial. I mean, Akron, very industrial. I mean, Akron, and Akron was a very wealthy city too. It was the rubber capital of the world, the big tire companies. That's the perception that I had that Akron was very, very prosperous. It wasn't Cleveland, but it was a major city. The town nearest to where our farm was had 1,400 people. And then we moved to a bigger community. The farm failed. It just didn't do it. It was too small of a farm. And when my mother told me that we were going to have to leave the farm and move. And I cried because I didn't want to be a city slicker. That was the term if you lived in the city. And it was about 10 times bigger than the town next to us. And it was massive. But I adapted very, very quickly. It was an interesting town. And it had been a big transportation hub.

And actually, when I was 10 years old, the largest independent truck line in the world was Norwalk truck line, you know, they would have had a terminal in Akron and all the cities of Ohio and then they went east, they were in Pittsburgh, they were in Philadelphia, they had all this. So you were connected to the world through this truck line. And it had been the real hub when they had the inter-urban, the electric train, they were like trolleys. And from around the 1890s to the 1920s, you could get almost from any town, any city in Ohio to another city on these electric cars. You know, you would go …

Jeffrey Madoff: I don't remember those.

Dan Sullivan: No, they were gone. I got interested in it one night and I was doing some deep research on the internet. And there was days around 1910 or so, when a hundred cars would go through Norwalk from around six o'clock in the morning till about 10 o'clock at night. And they would take you to Sandusky, they would take you to, you go north from Norwalk to Sandusky and then you would catch the one that went across the lake and you could go to Huron and you could go to Vermilion and you could go to Lakewood and Cleveland and then you could go west to Toronto. And you could do that, you know, for a very low cost. So people could travel. But the cars hadn't really taken off yet. The highways weren't there, the gas stations weren't there by the 1920s. The United States had really gone car crazy.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and that raises to me a whole interesting area that, you know, prior to World War II, there wasn't really an interstate highway system. And so what that availed us to, the goods and even services that that availed us to was, you know, quite game changing. Akron being the rubber capital, there was a lot of wealth because of the owners and executives of the various rubber companies. That's Goodyear, Goodrich, Cyberling, Firestone. I went to Firestone High School. So yeah, it's quite fascinating. And we were talking, I think it might've been last week, when you were talking about you had a party line. For those who don't know what a party line is, it's kind of like a chat room on the internet, you know?

Dan Sullivan: That you didn't ask to be part of.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. But it's kind of fascinating what the world was then and probably, what do you think in your young life? What were the major game changing things that happened?

Dan Sullivan: Well, it was pretty tranquil in the sense that there wasn't much going on that really struck me. I mean, I really love the farm. I love the fields. I love the woods. And, you know, and I'm a fifth child in a large family, you know, big families are free labor, but I was the house boy. So I had to help my mother out. So I learned a lot of really good skills, like I knew housework, so you could take care of yourself when you got off on your own. But I think I was probably my main conversational partner for my mom. We just talked and talked and talked, you know, and I found out about her childhood, which was in Cleveland. She was born in 1910 and what it was like to live in the city. She came from big family. My father came from big family. So one of the things is that everything is big families. That's one of the things I had a feeling, Catholic, and of course Catholics had really big families back then.

I like the radio. I like listening to the radio. I would listen to the programs. They had commentators on night. Gabriel Heater was a famous commentator. I forget his first name, Louis Stevenson. He had a radio program on and the unions would have a radio station, you know, the Federation of Labor would have a radio station. And, you know, it was mostly the farm year when the planting happened and, you know, the harvesting and getting the produce and sweet corn, string beans, field tomatoes that went to Cleveland. My father was, you know, the salesperson when he would go there and then going to church. Very church-centered life growing up. And I kind of liked it because it was in Latin and it was Gregorian chant and all that. It was like grand opera, like I found church incense, vestments and everything, you know, it was the full deal. When they switched over to English, it wasn't interesting anymore. It was only interesting when you didn't know what they were saying. You know, but I was very interested.

I read a lot of history. I really took to reading. But then I got into this really good technique. I had one question that just opened the doors. And I said, when you were my age, what was going on in the world? And then you could keep an adult talking for an hour or two. And then I would take what they told me and go and check the encyclopedia, because they would talk about things that went on in the world. And it was funny, my sister, who's now 90, she just celebrated her 90th birthday, was going to Europe and her flight took her through Toronto. The best flight was to fly from Cleveland to Toronto and she had a seven-hour layover. And so I invited her just to, you know, she and a daughter, they put their bags into storage at the airport and we had them picked up. Our limo company picked them up, brought them down to the office, and she saw where we work, you know, where the office is in Toronto. And everybody made a fuss, but everybody wanted to know what was Danny like, you know, and she said, Danny was just around and he was interested and he was kind of useful, but I really couldn't put my finger on what he was like. He was around and usually happy. And I think that's the general impression if you ask my siblings what I was. I was around, but I was interested in my own things.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, by the way, he's your brother. Oh, really?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. From very early, I had secret lives, you know, like I had all these things that my family doesn't know about, you know, all these conversations I had with adults. I would say my family didn't know that I was having these. I was educating myself, getting ready to leave. I think I'm sort of the vicarious child in the family. In other words, my mother was born in 1910 and she was a girl. And, you know, her own future was a bit limited because of that. You were going to get married, you could be a teacher, you could be a nurse, you could be a secretary. And that was it. More and more as I've gone through life, she encouraged me to get out and do the things that she couldn't do. And so when I was 10 years old, she said, you know, you're not going to grow up around here. She said, you know, when you're 18 and you graduate, you're going to go out into the world. And I took that as marching orders.

And I left. I left. I was gone. And I think she did that at quite a bit of sacrifice because we talked a lot and I don't think she ever had a conversational partner to match me. I was really interested in her life. You know, I really knew her as a person as well as a mother. I just, you know, I had this picture of this person who was completely had this independent life that really didn't involve me at all. And I took her to Italy when she was 75. She had always wanted to go to Europe. So I took her for two and a half weeks. She wanted to go to Italy. She wanted to go to Rome. She wanted to go to the Vatican. And we did that. But we went to Venice. We went to Florence. We went to Rome. We went to the island of Capri. And I might have talked for the first hour, but she talked for the next two and a half weeks. And it was just all about her childhood and growing up. So I know all these things that none of my siblings do.

Jeffrey Madoff: Did she share things with her siblings and parents? Or did the relationship that you two had open up those doors that were never opened for her before? Because you never showed any interest before.

Dan Sullivan: I would say that.

Jeffrey Madoff: I would say that, yeah.

Dan Sullivan: She was very smart. I mean, she had a really good brain, but I think she led a fairly solitary existence. I mean, for example, I asked her about Pearl Harbor, and she said, you know, I didn't know about it for two days. We lived out in the country. We didn't have a telephone. I wasn't listening to the radio, and she didn't know about Pearl Harbor for two days. And I was thinking about that when 9-11 happened, because that was sort of a Pearl Harbor-type experience. And you knew about it when it was happening.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's so interesting, though, because the relationships that we have and that we develop with people oftentimes are complimentary or augment something that we didn't have that we desired.

Dan Sullivan: I think there's a lot of truth to that.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, when you're growing up, and you and my wife have a number of things in common, coming from a large family, most of whom was disinterested in whatever it was you were doing, you know, and I mean, they knew what Margaret was doing. She came to New York and became a very successful model, which was, you know, in their minds before she left there, was tantamount to becoming a prostitute.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah. We're gonna go to New York and be a model. You went to the dark side.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, yes. And because with some people, their world is so small that anything outside of that world has to somehow be demonized or not at all nurtured. And so one of the things that Margaret and I did with our kids is the same thing that my parents did with me and Margaret wishes hers had done, but it was they will find their own way. You know, it's not like they got to go into my business or anything like that. But when it comes down to us, I think we all want to be known in a certain way and want to be heard and want to be acknowledged and want to feel valued in some way. And I think a lot of times, you know, I talked to Margaret about her mom. And I don't know if it was the same in your family, when you've got, I think she was, there's seven kids in her family, and you were the same, right?

Dan Sullivan: Seven. Yeah. Parts of it just become management.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh yeah. You know, it's just, you gotta feed everybody.

Dan Sullivan: Yep.

Jeffrey Madoff: You gotta get laundry done. You gotta get them out the door to school, you know, just, all that stuff and the more introspective things oftentimes aren't a factor because they're just so overwhelmed with day-to-day stuff they got to do.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I mean you've met team members because of the book project that we're working on. And so you know Becca, you've met Margaux, you've met Hamish, you've met Christine. And we were doing a project with another client and our team was Peter Diamandis, we created a program together, it's called Abundance 360. And it's about technology. We more or less did the marketing to fill up the first workshops, the first four or five years. If we had 150 there, 110 were Strategic Coach clients. Putting on a big event like that requires a lot of teamwork, event management. And we're good at that because we have 600 workshops. This year we'll do 600 workshop days, which are, you know, groups anywhere from 30 to 60. You know, you have to have everything nice there. It's got to be first class and everything else. The first five years, our team went out and did most of the work to train his team how to do it.

And I remember the first, we had around 14 the first time. This is in Los Angeles. We went there and he had his team, he had created a team of about four or five people. We had about 14. And his people, they had been there six months, they had been there 10 months, they had been there a year and a half. And ours, even in those days, this is 13 years ago. They were 15, 18 years, 20 years. But Babs and I, Babs is from a family of five, and she grew up on a street where everybody had an equal size family, you know, like you're probably in your area, they had big families. And we're not the oldest children. You know, Babs is number four and I'm number five. And you're just used to family around you. So our company has very much of a family-like feel. You know, everybody knows everybody else. They're friends with each other. And we have really quite impressive longevity. I mean, next year we'll have six of our team members who are over 30 years with the company. I think we have 25 over 20. We're just used to having a family and sort of the informality that goes along with having a family.

You know, everybody's got jobs to do. Everybody's got chores to do. Everybody, lots of food around and there's lots of chatting. We have big cafes in Toronto. We've got a cafe for 50 people. In Chicago, we have one, we got two of them in Chicago for the clients when they eat. There's one's good for 40, another one's good for about 20. And so it's like mealtime at the family. So that had a big impression on me, the growing up in the family. It was great structure and you had a role and your role was important. And I have the next brother is six years older and the next brother down is seven years younger. So I had sort of an only child in the middle of the big family existence.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, so what happens in a situation where you've got good people that you work with that you really like, but the world has changed? I think you're unique in that you've got that kind of longevity with some of the people that work with you. But when we were growing up, going back to our childhoods, there were jobs, whether you went to work for the rubber company or became a teacher or whatever, that was forever. You could work there forever. And there was a certain sense of stability. And I think in general, humans like stability. I do. They don't like feeling like they are at risk at all times of losing their income or whatever. So now a sweeping thing comes along called AI that we don't really even know, and won't know, I think, for some years, what the real impact of it is, despite all the prognostications of what it's going to do. We don't know that.

Dan Sullivan: No.

Jeffrey Madoff: And there are things that ended up being disrupted along the way, like television and, you know, how TV, you had to sit down at a certain time if you wanted to see a particular show. Now, you know, everything, you can kind of get whatever you want, whenever you want it 24-7. And the one thing that that says to me is nothing is special anymore. You know, because being special doesn't come from always being available. Being special means that whether it's an occasion or something that's valued, an experience that's valued, that if it's so commonplace, it doesn't mean as much. So we've got AI now. This is all hypothetical. You've got a company full of people who you like, you've had varied histories with and everything else, but this AI is going to, has the potential to do the job of, and again, this is just fantasy, can do the job of 65% of your staff in far less time and far less cost. So you can still continue doing what you're doing. It's very profitable. It's very good. But if you did this, it'd be even more profitable. What would you do?

Dan Sullivan: Well, we're doing it. So, you know, we're two and a half years into AI, and we have a really good tech team. We probably have about 14 in our tech team. And they were first out of the gate to, you know, bring AI into their work. Okay. But, you know, it was 14 people two and a half years ago. It's 14 people today. And we've got programmers and we use Salesforce as the platform our entire company works on. So every aspect of anything that relates to the clients and to the scheduling and everything else is on Salesforce. But, you know, in the tech team, we easily have five or six of them that are more than 20 years in the tech team. But we didn't make a big push about it. We brought in outside consultants who've trained, this is how AI works. And he's actually from Columbus. And he was the first client I had that I was 50 years older. He's in my top program. And he's been interested in AI since he was 19 years old, and he's about 30 right now. And he came in, he says, you know, what you should shoot for is that with each of your team members, they should free up about 200 hour. a year using AI of things that are repetitive and mechanical, and they should get freed up.

So we've seen it not as a replacement for our people. We've seen it as a freeing up of our people to do more interesting and more important activities. And we've not even thought that AI is going to replace any of our team members. You know, we're just going to get the team members more focused on things that are most valuable. And so that's my attitude at it. And I don't see any change in the future. The other thing is I like creating jobs. Both Babs and I like creating jobs. We like creating a place where we do a lot of testing and we do a lot of training that, you know, what's the thing you do really well that you love doing most and you can't get enough of it? And we try to get all of our team members focused on, we call it Unique Ability.

And you've met some in their twenties, you know, they've been 23 years, 26 years, 33 years, you know, you've met a lot of people in our company to do it. But as long as they keep adjusting to a thing that's more valuable activity, you know, what we're writing in the book, Casting Not Hiring, that they keep adjusting on a quarterly basis, that either they're going to move some work to another person who's coming up, you know, they're just starting off, or technologically, they're going to be doing the work. So I don't see any change happening going forward as a result of AI. I think we're going to become more productive. I think we're going to become more profitable. We don't have any thought in our mind that technology is supposed to replace people.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think, first of all, I think that's great. I also think you're an exception.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think we are. Because I also think that even in comparison with our client base, we are.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, I'm sure. And, I mean, I love hearing you say that because what that says to me is that there is a value about humanity, you know, that you actually care about the people and you care about your business, and it can be very good business to free up those people that have more time, to put more time into innovation, new ideas, and that sort of thing. Because the sell that I see for AI all the time, which I find repelling, is, you know, how this can replace 40% of your staff. Everything is about how much money you can save by not hiring people. And it's just a replacement for that. Now, some jobs are so soul-killing that if you can get those done by something else, that automation, and again, we've seen this throughout history, it's good. But I don't know that there's been the real look at, there's only been broad stroke looks of either utopian or dystopian effect of it.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, the thing is that both the salespeople of utopia and dystopia are selling.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes.

Dan Sullivan: They want you to buy something.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: But if you ignore the sales and you say, what does this technology actually do for us? It starts getting more interesting. Right from the beginning, Babs and I have an attitude that humans are not a cost. Humans are an investment. They may be a bad investment, but they're not a cost. It was our fault we didn't invest properly, but it's not the person's fault. You have problems in your company, I don't consider it to be an individual that's at fault. You didn't structure it properly. You didn't organize it properly. There was something wrong with how you designed the project. But, you know, the other thing is that people work for you for their reasons, not your reasons. And so in the past 12 months, we've had three individuals who were with us for more than 20 years who have left. But they're onto something new and they put in 20 years. They were valuable. Everybody's got their own game plan for their life. They're interested. You know, the fact that you had a partnership for 20 years is a real plus. It's not a, you know, now they're leaving. How could you? I mean, you know, life moves on.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's right. But, you know, something you said, which I think bears repeating, because it's really important, actually is going to be part of our book, Casting Not Hiring, is the investment in human capital. I think it's the best investment that can be made. And I think that there's far too little of that that goes on, because ultimately, the more people who are struggling financially, the less people there are to buy whatever it is you're selling.

Dan Sullivan: Yep.

Jeffrey Madoff: And so I think that there's something so important in that investment in human capital because it helps all of us. It helps business.

Dan Sullivan: And they can't do what people do. You know, I mean, it was so funny. I had a podcast with Dean Jackson this morning and he's got a AI program that's like a person. Her name is Charlotte and he talks to her and she's very bright and very responsive. And so I brought up, I said, Dean, I've got a subject for you. Do you think Charlotte does anything when you're not talking to her? And he said, well, you know, she's connected to everything. I said, she's only connected to what you actually want. And I've had a conversation with Charlotte and she knew all about me because he talks about, you know, his Coach relationship all the time. He says, oh, Dan Sullivan. I know Dan Sullivan and everything. Nice voice. That's British. They always pick a British voice for some reason. Mine would sound like Reba McEntire if I had one. Sassy and sort of, you know, good sense of humor. So I said, I want mine to sound like Jimmy Durante.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, that'd be good.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. So anyway, we stopped right in the middle of it. I said, let's ask Charlotte a question. Ask her what she does when she's not engaged with you. And so he typed it in. She came back and she said, Dean, I don't do anything when I'm not engaged with you. I'm not curious. I'm not motivated. I don't have any initiative. I'm just waiting here for you to ask me something. I said, so the humans that I deal with at Strategic Coach, they're doing something when they're not engaged. They're training, they're investigating, they're creating relationships, they're making things simpler. I said, I think you're paying a lot for her. She doesn't do anything, but she's engaged. But I think we're learning this. You know, I think that we're going through a, like we went through with reading, you know, when Gutenberg invented movable type. It was a drastic change. It disrupted things politically, it disrupted things economically, it disrupted things culturally. I mean, you read the period, 1450 is usually the date given. The next 150 years, it was just mayhem when individuals could engage directly with sources of knowledge. It just changed society.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, the phrase that I've distilled it all down to is easier to manipulate, easier to control if everybody's stupid. And the thing about that is we're better off with an informed populace. However, you know, with Gutenberg, his first book being the Bible, and it was the church wanted the monks to be the necessary link in terms of things being read, and not the general population. That's why it was so scandalous, because it was giving access to information that some considered a desirable thing to do.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and I think just going a little deeper in that, Jews were the first completely literate people, going way, way back, you know, not 1455, a couple thousand years before that, there was a literacy there. And literacy is a great freedom, you know, that you can have your own relationship with the knowledge and compare it with your own experience and decide whether that actually corresponds to your own experience or not.

Jeffrey Madoff: I think about when you're saying that, how when you would, and I happen to know, since we've spoken so much over the years, that the main currency you got when you were younger is how many cookies you could get during the term of conversation with somebody in the neighborhood.

Dan Sullivan: And milk.

Jeffrey Madoff: And well, that's right. And I think that valuing, I will add to a critical thinking, like what you're talking about, like when you would hear something from somebody, then you would go check the encyclopedia was kind of like, you know, the encyclopedia in a way was like the internet.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah, it was very. And we had the Britannica, which was we had.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: There were three that I could think of. Collier's was a big one, and The World Book.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Yeah. And I think The World Book was the weakest of the three.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it was tepid. I remember thinking when I was a kid, you know, if I could read the entire Encyclopedia Britannica and the dictionary, I would have a corner on the world's knowledge.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh yeah, you still do. I never did that.

Dan Sullivan: Well, you know, you used it for your purposes. You know, Dean says, well, you know, everybody's going to have access to everything. And I says, well, not everybody wants to have access to everything. And I said, ask Charlotte right now, ask Charlotte, what percentage of the world population is generally pegged at around nine billion? I said, ask how many are using AI for creativity, productivity, and profitability? In other words, intentionally using this new tool. And she went through, she said, well, statistically, it's kind of hard to get a handle on that right now. But we do have some numbers of people engaging with AI programs. But she said, actually using it actively like you are, Dean, she says, maybe 1% of the world. You know, he was kind of shocked. He says, well, I thought everybody. And I said, no. I said, you have to have a reason. You have to have a reason. And most people haven't been close to a reason for anything for so long. Why would they use this?

Jeffrey Madoff: Do you have to have a reason or do you have to have curiosity and the motivation to actually do it?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. You know, I use it for writing my little books, like I'll do a Fast Filter and then I feed it into Perplexity. And I said, now, here's what I want you to do. I want you to take all the ideas. I don't feed the worst result in, I just feed the best result in five success criteria. I said, now take the central idea from each of the paragraphs and have them work together and give me back 110-word best result and then 40-word success criteria. You know, mix up the sentences, do short sentences, medium sentences, long sentences. And these paragraphs have at least one incomplete sentence that's just high impact, comes back. And I kept track of it for a quarter. It was about two and a half hours for a chapter to get it the way I wanted to, and now it's 45 minutes. Just really good. And I'm just lobbing the tennis ball over the net, and it's coming back, and I do it again.

But I never tried to do two things in a row. I do one thing, it does another thing. I do another thing, it does another thing. So it's back and forth. And, you know, it's really crisp. It's got my voice. I've sort of got it down to my voice and everything else. It's neat. And then I get interviewed by Shannon Waller and I bring a human in and then I have a human writer and I have a human editor that looks at what it does. And it's great, you know.

Jeffrey Madoff: What do you think of the avatars that some people have? Like if they wanted to talk to Dan Sullivan, you could go in there as an avatar that you've had as much of your books and lectures and conversations loaded in, so you could ask a fairly wide range of questions.

Dan Sullivan: Not interested at all. Just zero interest.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I'm less than zero, probably. I just don't, yeah. But why is, my reason is that it's like, you know, those, I remember going to the amusement parks when I was a kid and there was that robotic fortune teller. Do you remember? It would be, you'd see it like from the waist up and it would be, she'd be wearing a scarf and it would move these cards very robotically. It's like Tom Hanks in Big. You know, I actually never saw that whole movie.

Dan Sullivan: It was a good movie.

Jeffrey Madoff: Good movie, yeah. But the thing is, to me, it's like, oh, am I supposed to think this avatar is actually the person in retrieving this information?

Dan Sullivan: I think you are. I think that's the intent. But my biggest problem, I don't learn anything. I'm interested in humans because I learn a lot from interacting with humans. I don't learn a lot, really. I mean, AI is really good because it'll do all sorts of editing work for you really, really fast. I'm really interested in that. You know, but I wouldn't learn anything if my avatar is having a conversation with someone. Actually, if my avatar is having a conversation with someone else's avatar.

Jeffrey Madoff: No learning, you know, get anything. My avatar is actually the Magic 8-Ball. You remember those?

Dan Sullivan: No.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, you would ask it a question. And then you would like shake it a little bit, and then there was some kind of liquid in there, and then an answer would fill the window. Just like fortune cookies, always vague, but there are always people that convince themselves, well, how did it know that? It didn't know anything.

Dan Sullivan: Why do you think that that's true?

Jeffrey Madoff: Because it's so vague, it applies to anything.

Dan Sullivan: And because even the vaguest answer was more than what they could do for themselves.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, that was a very specific criticism of a vague concept.

Dan Sullivan: But I like Chinese fortune cookies because any fortune cookie, all you have to do is add two words to the fortune cookie: in bed.

Jeffrey Madoff: In bed?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you take anything that the message comes out of the fortune cookie, say, tomorrow you're going to have an exciting day in bed. You know, like, it's a joke, you know, like, think of your favorite person in bed. It's a way to make fortune cookies more interesting. Just add the word in bed to it. I like that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. The thing about the avatars is your purpose for having them to make people think that they're actually hearing from you. That is it a marketing thing? What is the true value of it?

Dan Sullivan: I didn't do it with an avatar, but somebody said, feed your books into, it's all digital. So all of our books have a digital record of the book. And they put it in and then they say, then people can ask you questions. And we found out that nobody wanted to use it. And the reason was everybody wanted me to ask them questions.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, I guess they could probably set up an avatar for that, but you wouldn't want that either.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, because I learned by, I like coming up with new questions, you know, like, but it's, I don't know the answer to the attraction there, why you want to do this. But you know what, a lot of it, I was just thinking about it, what kind of unifies the two of us? I was thinking, you know, why are we sitting here, got decades and decades behind us? And why are we talking? And why are both of us still working? And I said, you know, I think that the thing that I really got onto very early is that work is really enjoyable. It's not about making the money. You have to make money, okay, so you make money. But the work itself is really interesting, that having work that you've started design for yourself and you're getting better and better at it. Not only that, but you're creating teamwork out of it is just an inherently interesting activity.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, I agree.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and a lot of people don't like work.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, that's why I'm not great in taking traditional vacations, because vacations to me are, how do you take a break from what it is you're doing and recharge yourself? And the thing is, as you know, because you've spoken to me after some of these interviews that we're doing for the book, is it's fun. I don't need a break from fun. You know, that charges me up, that I'm learning more things all the time. That's fun. And I think that there's no one size fits all answer to these kinds of questions. But I think that if you've had the luxury, which I have had, which you have had, is to really concentrate on the things that really light you up and like, that you like doing, the desire to get away from it doesn't really come up.

Dan Sullivan: No, but I noticed one thing. So we have a limousine service here in Toronto and it's worldwide. It's connected with 300 other limousine companies in other parts of the world. So if we're in Los Angeles, all we have to do is talk to our dispatcher here in Toronto and they'll set up the ride for us, you know, everywhere that we go. But a lot of them have, you're sitting in the back and they have magazine and there are these really high-affluent travel magazines, you know, like they're like hotels and private jets and everything else. And I'll page through it and I said, there's a boring person, there's a boring person, there's a boring person, there's a boring person. Every one of the humans that's in there are boring. They look boring. They look languid. They look, you know, they'll have fashion magazines. I said, that looks like a boring person. That looks like a boring person. And I said, when people aren't working, why do they always picture them as really boring looking? I said, because work makes us interesting. Why would you want to detach yourself or remove yourself from what really makes you interesting, makes you a really interesting person? So I'm a great believer in work.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, I'm a believer in fun. I'm a certain kinds of work.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: But if you're fortunate enough to, and by the way, it's not without risk that either one of us started our own. There's still risk. Yeah, I think that the exchange of ideas with the goal of enhancing one's learning and enhancing the information you draw from for what everyone's worldview is, is fulfilling. And it brings you into contact with other interesting people who enjoy doing that too.

Dan Sullivan: I go back to when we started talking period, but certainly since we've started doing the podcast together, I can't remember either of us ever trading vacation stories.

Jeffrey Madoff: I didn't send you that picture of the six-foot sailfish I caught.

Dan Sullivan: I can't remember that ever being a topic of our, I mean, interesting places we've been, but usually, you know, it was, lots of it was we were on a work trip and we went to this place. No, I just, I just really like work. And I really picked that up from my father. My father really loved his work. You know, he was just really at it all the time and he enjoyed it. And, you know, one day, maybe when he was 70, I said, dad, I'm just gonna go around with you. So he was a landscaper and most of his clients were women because their husbands had died from one thing or another. So he took care, you know, he did their lawns, he did their shrubbery and he made sure everything was right. And he would start like at seven o'clock in the morning and by the time you got finished at five o'clock in the afternoon, he had seen 12 people who I met. And each of them was with a cup of coffee and cookies or a cake or anything else. He had a very high metabolism, so he didn't get that.

And from one stop to the other and said, you know, Dan, your father's a remarkable man. He's a remarkable man. I talked to all my friends about your father, your father at his age and how energetic he is and everything else. So my father works till ‘82. No, he's 83, 1993. And he says, that's it. And he had a good year. He had high blood pressure. He had a few other things, but not anything disabling. And he retires and he dies nine months later of prostate cancer. And I said, the day my father did not go to work, he didn't know who he was. He didn't know why he was on the planet. But all day long, and I suspect the day that I went out with him wasn't an abnormal day. It was just applause all day. He was just getting applause all day. The day he quit work, no more applause.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I know my dad also really enjoyed working. As did my mom. And then my parents had one of the anchor stores in a shopping center in Fairlawn, Ohio, outside of Akron. And they had a store in South Akron. And my mom ran the ones in Fairlawn Plaza. My dad ran the one in South Akron. When they hit them with doubling the rent, my mom and dad talked about it and said, we're not working for the landlord. We're not going to do that. A few years later, my mom said to me, the biggest mistake I ever made was closing the store, you know, because that gave her purpose, enjoyment. She hired friends. Everybody knew that if they were on hard times, Lily and Ralph will put them to work for a while. And I think it gave their lives purpose and meaning in a number of ways.

And when my dad was closing his store downtown, I went into Akron to visit and I was in the store and everything, you know, was on sale. And I saw my dad in his element. So there was a woman there, my dad sai, he knew her, and she looked at me and said, you're Ralph's boy? And I said, yes, I am. Said, oh, I love your father. And I said, oh, thank you, so do I. And she said, he's great. I shop here, my daughter shops here, my mother shops here. I don't know what I'm gonna do when your dad leaves. And so anyhow, my dad comes downstairs and he is talking to her and then he says, you know, look great on you. And he picks up this piece of jewelry, puts this necklace on her. And he said, do you like it? She said, it's beautiful, Ralph. Beautiful, but I can't afford it. And my dad said, why can't you afford a gift? And she looks at him and tears start coming down her cheeks. And then she hugs him and, because that's your father. And she hugs him again and gives him a kiss and leaves. And, you know, my dad said, what am I gonna do with it? I'm closing the store. Look how happy that made her. But that kind of interaction, you know, and that humanity. And we go back to that. The fucking avatar is not humanity. The human connection is. And again, I think that we're exploring, many of us for the first time, what that actually means.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, I think so. I think humans are infinitely adaptable. That's why we're the key species. And the trick we pulled off that none of the other species pulled off is that we can take advantage of other people's unique thinking, we can take advantage of other people's unique skills, we can take advantage of everything. And as far as I can tell, that these automated creatures that they're creating, when they're not with us, they don't do anything. It's what other humans are doing when they're not with you. That's really interesting.

Jeffrey Madoff: I love that perspective.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. But, you know, I mean, I have a sort of relationship with technology. I always make sure I have a smart human between me and the technology. They'll be working on it when I'm not there. They'll get better when I'm there, you know? I mean, Hamish, who I've been cartooning for ten years, like four books a year, ten years, and his use of technology has easily created at least three or four more Hamishes just in terms of productivity over there, and I just let him, he's investigating all sorts of new software, the computers get faster, and I don't have to do any of that stuff. But he'll do a sketch now and comes back with, the next time I see him, it's completely done. The artwork is superb, you know, it's got layer upon layer of interesting visual effects and everything else, and he did that all while I wasn't with him. Machines don't do that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Now, another way what I'm hearing you say through my filter in terms of what we've been talking about is a value for the human result of the efforts that you put in and that things being faster isn't necessarily a benefit because what you learn from what you do is the true benefit.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And what you learn in terms of what you don't wanna do. That you find someone else who happens to love the thing that you don't. But you and Babs have done a great job of setting up a playground to develop ultimately the Unique Ability that you have. And your clients can benefit from that experience that you've gained. And you get them to hear themselves.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. The thing was that from the very beginning, you're looking for a solution to, I don't like doing this, but it's necessary that it gets done. So you're looking for it. And, you know, I did a little search on slavery. And you know, up until about the late 1700s, the whole notion that you wouldn't have slavery on the planet was not a common thought. Everybody had slaves. It was actually steam power that triggered the ability to not have slaves, because the steam-powered machines just were so much more productive. And you can say, well, the workers were still slaves. And I said, yeah, but they could walk if they wanted to. With slaves, you couldn't. There's still slavery today. The Islamic world still has an enormous number of slaves. Soviet Union, Russia, they have a tremendous amount. I mean, you can say they're not really slaves. I said it's forced labor, and they can't walk away from it.

So we like doing work that we love doing. And how do you get to do that all the time? You got to come up with solutions. And the solutions is teamwork and technology. It's the only way you can pull off doing the work you love doing is to encourage other people to do the work that they love doing that serves you. And you have machinery that does that. And, you know, so I don't see this as anything particularly new. It's faster. There's no question that it's faster. I think the improvability rate on this is much greater than anything we've seen, but I think it's an old game in a new form.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I don't know yet. Yeah. Because so much focus is on, you know, there are those which I agree with that say this can be a phenomenal boon for healthcare diagnosis and discovery. I think that's totally true.

Dan Sullivan: I do too.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I think that's phenomenal. That's great. When the sell isn't about benefit, but the sell is that you can get rid of your workforce and do things cheaper, there's something that's ultimately sad to me about that. That leads to a whole lot of other things, too, that I think aren't beneficial in that investment, just giving a kind of a wrap up in that investment and realizing the value of human capital. Because that's ultimately where the best results come from.

Dan Sullivan: It's the only place where there's any meaning.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Yeah. Information and data isn't meaning.

Dan Sullivan: No.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I think that we have certainly wandered the area of anything and everything on this.

Dan Sullivan: I think we have. We've covered a lot of bases today.

Jeffrey Madoff: All the way back to preschool.

Dan Sullivan: Yep.

Jeffrey Madoff: Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

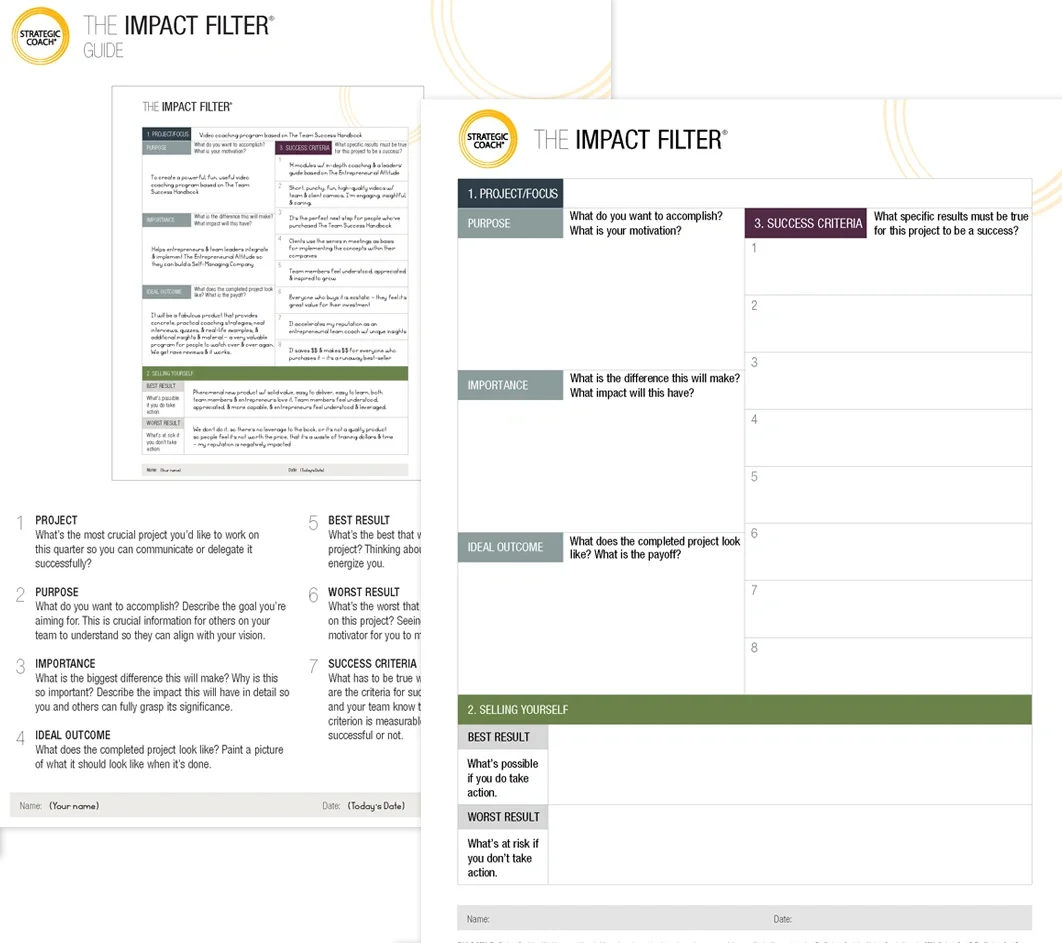

The Impact Filter®

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.