Keeping Your Momentum Strong When The Future Is Foggy

December 09, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Steve Krein

Steve Krein

The world’s changing faster than ever, and predicting what’s next is tougher than it used to be. But some entrepreneurial truths hold steady. Dan Sullivan and Steven Krein explore how staying ambitious, embracing fresh possibilities, and surrounding yourself with the right people lets you keep setting bigger goals no matter what the future brings.

Show Notes:

New technologies unlock new entrepreneurial capabilities, giving you more ways to grow.

Economic policy shifts, like recent tariffs, signal consumption is now more important than production in the U.S.

The U.S. is the greatest consumer economy in the history of the world.

Over just the last six months, the strength of your consumer base became the new measure of future success.

Predicting the future based only on past trends is getting harder, as possibilities matter more now than probabilities.

Rapid change means it’s a whole new game; fresh opportunities are opening up for the next decade and beyond.

Retiring can create social friction because if you’re working and your friends aren’t, you have less in common to discuss.

Ambition is the opposite of envy.

Surround yourself with other ambitious thinkers; your environment shapes how far you’ll go.

Resources:

Always More Ambitious by Dan Sullivan

Ambition Scorecard by Dan Sullivan

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas Kuhn

Bill Of Rights Economy by Dan Sullivan

Episode Transcript

Steven Krein: Hi, this is Steven Krein with Dan Sullivan for our latest episode of the Free Zone podcast. Dan, it's good to see you.

Dan Sullivan: Good to see you, Steve. Exciting times.

Steven Krein: Very exciting times. And I think that the perspective of the exciting times coupled with your last quarter or so that you've been focusing on ambition and your last quarterly book about ambition and today the conversation about ambition could not be more appropriate than it is right now.

Dan Sullivan: You know, technology has always really been part. We've lived, you and I, our entrepreneurial lives where you keep experiences that new capabilities are available. You know, when I became an entrepreneur in the ‘70s, 1974, you know, you didn't have the technology. Just think about running a company in the 1970s as compared to when personal computers came in, software came in, the internet came in, mobile communications, and now we have AI. If you put 50 years together, it really surprises me that if you are ambitious and you know how to put good teamwork together and you have technology, there's no reason why you wouldn't become more ambitious as an entrepreneur if you keep your health good, you know, if you have physical energy and you keep making bigger and bigger goals. But I'm noticing that there's a gravity from the past where people are saying, yeah, I'll work into my sixties and then I'll pack it in. And I say, well, why would you do that? I mean, what are you going to do when you don't have a company? What are you going to do when you don't have deadlines? What are you going to do when there's not the possibility of creating new solutions?

Steven Krein: It's interesting. I was thinking a lot about this as it relates to AI, and in particular, the discussion around how much of AI is based on probability versus possibility. And the idea that there's so much inherent in the past that is relied on for business, for entrepreneurial activities. And I think that there was a period of time, probably a long period of time, where you could use a lot of the either far past or even recent past to predict what's coming next. And I feel like, indicative, by the way, of what's going on all over the world, it's very difficult to predict the future based on the past now. And the possibilities that exist now are pretty exciting and I think are creating, you know, regardless of age, a new view of what is possible over the next decade or two at either individual level or a business level.

Dan Sullivan: There's been a huge switch globally and it's just a function of Trump coming in as President the second time and it had to do with his use of tariffs. It's a very, very interesting thing because all the experts, the people who know about these things, who have looked at the use of tariffs in the past said this is going to be a disaster, we're going to be in a depression. And it's something that I've been paying attention to just as an entrepreneur and an observer of things, that what Trump was betting on was that it's now consumption that's more important than production. Basically, that another country will pay a 25% tariff on their production, you know, they're producing a product, they're trying to get it into the United States, and they're willing to pay 25% just to get their product to American consumption. It's the greatest consumption economy in the history of the world, just numbers are big, you know, it's the third largest country, you have China and India, then the next, the United States is the third largest production. But these are wealthy individuals, and I think this is a huge shift.

Like, for example, I live both in Canada and the United States, mostly in Canada, and the Canadians don't understand what's happening. And I pointed out to them, I said, the state of Texas has an economy that's 50% larger than the economy of Canada. State of Texas. I'm not talking about the other 49 states. I'm just talking about Texas. It's 50% bigger. Population isn't as big. Canada's about 40 million, Texas about 30 million. But I said, these are big consumers. These are really big consumers. So if you don't even match up with one of their, not the biggest state, if you don't even match up with one of their states, you got the 49 other states, and you were just taking a look at consumption, well, do you want to do business in Canada or do business in the United States?

And so it's really interesting that we have crossed a line. I think we've crossed a line just in the last six months where the future now is how good of a consumer population do you have? How big is it? What's the per capita income? And what do they spend? And that's a shift. And I think the other reason, because I'd like to tie it back into your AI thing, with AI, you know every time a credit card is used, you know every time a check is written, you know that a transaction has just happened. So I think that's a big shift. I think that's a momentous shift in consciousness. You won't be going back to a world before these tariffs went in. I think this is the start of an entire new geopolitical reality.

Steven Krein: If you bring this back to ambition, and I feel like what we're talking about before we started recording, you've been talking about ambition for a long time. You had a book in the beginning of your quarterly books called The Ambition Scorecard?

Dan Sullivan: The Ambition Scorecard, yeah.

Steven Krein: And your latest quarterly book is about ambition. And now at 81 years old, your perspective on it seems to be a very important factor in why you're both revisiting it and what's changed about it when you either look back at the Ambition Scorecard or why your renewed, I don't want to call it obsession, but interest in reframing everything around ambition. Tell me a little bit about that.

Dan Sullivan: First of all, I think it has a function. It's partially a result of my age, because what I noticed when you hit 60, so for me, this is 21 years ago when I was 60, that all of a sudden the conversation is, so how long are you going to stay with, Dan? I mean, do you have succession plans? I mean, you're obviously thinking now of your retirement. And I actually wasn't. And I found that the pressure to go along with the norm was, you know, and maybe you're approaching that now because I'm …

Steven Krein: People retiring to Florida.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I think I'm 24 years older than you. You're 50.

Steven Krein: 55.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, you're, yeah, 55.

Dan Sullivan: Well, there's an intense pressure, first of all, just to hold on to your friends, because if you're still working and they're not working, you've lost some of the subjects that you can talk about, okay? So I think one of it is people want to hang on to their friends, and therefore they have to adopt a certain behavior that they all have in common, that we're going to stop working and then we'll get together and we'll talk about our previous business lives and whatever else retired people talk about. I'm not sure. When I got to 70, there was a release from this. And maybe it was just me that I had gotten through the decade when you're supposed to conform and I didn't conform. And then as I went through my seventies, I noticed it's just a function of what kind of teamwork—well, it's a function of who your customers and clients are.

And one of my experiences was, and I've got two of them now, where I've got two at the highest level of the Program who are 50 years younger than me. They're in their early thirties now. And I found it very interesting that entrepreneurs, it doesn't matter what age you are, it's just a function of what are you excited about, what are you working on, what are you doing new? And I said, I wonder how long I can keep going where it's just a function of, you know, what's the next big project that's bigger and better than anything you've done before? And I found if you take care of yourself physically, and we do a lot, Babs and I do a lot of medical, advanced medical stuff, but then, if you have really good teamwork around you, and these are all younger, these are 30-year-olds, 20, 30, 40-year-olds, it's not much different than it was before, but the technology keeps introducing exponentials, that you can do all sorts of things. I said, there's no reason for you to think old. Okay, so I think I'm really interested in is that I've gotten simplified, as long as I'm ambitious and I'm interacting with ambitious entrepreneurs, to a certain extent, I've eliminated the subject of aging and slowing down as something I have to talk about or pay attention to.

Steven Krein: Do you think it’s, just the word means something different at 81 to you than it did at 70 when you maybe wrote the book or maybe 73 when you wrote the book, but probably a decade before that when you came up with the concept? Do you think it's now a useful word to just, you know, mean a lot of different things that kind of get summarized into ambition? Because it used to be, I would think about mindset and how powerful [inaudible] mindset is versus skill set and how you either attract people with it. It's very binary, like batteries included versus batteries not included. We were talking a little bit about the same binary thing. What's the opposite of ambition? And I always love how you frame, you know, the batteries included versus batteries not included. I think when you have a transformational mindset versus a failure mindset, I think there's, you know, easy words for it to carry a lot of meaning, especially in our community. Tell me a little bit about ambition. What's the opposite of ambition and how do you easily detect it, just like you would detect somebody's energy?

Dan Sullivan: I'll have to tell a little story here. First of all, the word that I think is opposite of the ambition is envy, okay? And envy isn't jealousy. A lot of people use them as if they're the same word. Very interesting.

Steven Krein: So in the business world, do you think there's successful entrepreneurs who operate off of more envy than ambition? Or do you think it's you're very short-lived and it's not sustainable?

Dan Sullivan: Well, they can be really talented, so they can be successful in spite of their envy. In other words, they're just really, really good at what they do. But I think it's more of a social thing. It's more of a social status thing than it is marketplace competition. I think if you're involved in marketplace competition, you're playing the game and it's a very unequal world. There's always somebody who's got a new thing or everything. So I think you've adjusted yourself. I think it's more status. It could be within your family, for example, that a brother has success. I mean, in my family, that would be true. My success is greater than my whole family put together. You could go back three generations and my success probably matches three generations in terms of what I've done. So I don't talk about it.

Steven Krein: It's not at family get-togethers.

Dan Sullivan: Nope, we don't talk about that.

Steven Krein: So is it a mindset or is it a skill?

Dan Sullivan: What?

Steven Krein: Ambition versus envy. Is it a muscle? Is it a mindset? Is it a skill? Like, tell me a little bit about how you're thinking about it.

Dan Sullivan: Now that you're probing and you're going deeper on the subject, I think it's a status thing, that you're not as admired as someone else that's admired. I think it has more with social status. You know, and in the entrepreneurial world when you have sort of the social aspect of entrepreneurism, for example you belong to EO, Entrepreneurial Organization, but there's a social aspect of being an entrepreneur, you know, the fact that you are an entrepreneur, you're with other entrepreneurs, and you could have a lot of envy there. And it shows up in language. You know, someone is just enormously superior in a certain skill, it shows up. But I think it's a mindset. I had an interesting guy who was a financial advisor, and he married a Russian wife. And it was an internet meeting, and he married her. And he brought her in Chicago. He came to his workshop, and they came to dinner the night before. And I was sitting next to her, and she spoke really good English, so there was no problem.

So I kept asking her. I think her name was Evita or some name like that. And I said, Evita, tell me more about Russia. And she said, I will tell you a story about Russia. I will tell you one thing, and you won't have to know anything else about Russia. There are two farmers. They lived next to each other for 40 years. They each had a cow. One Monday, one of the farmers gets a second cow. On Tuesday, the farmer who still has one cow, goes to talk to the priest. He talks to the priest, says, I want to say a prayer to God. He explains, and the priest said, you want a second cow? He says, no, I want one of his cows to die. He said, that's all you need to know about Russia. That's pure envy.

Steven Krein: First of all, great story. I don't know the last time you told that. That's great. That's a perfect setup, actually. It's cultural. And it's around a community. I mean, I think about the community that we built at StartUp Health. I think about the community that you built at Strategic Coach. And I think about how special it is to surround yourself with always more ambitious people. I think there's something in the world in healthcare where I am, whether it's a mother, a father, a sister, a brother, a child, a spouse, themselves, that's been touched by a disease or an illness or a problem that they want to solve, and their ambition and their belief in what is possible is defying all probability. It's almost a driving force in our community that there is no lack of ambition. But when they go out to fundraise, when they go out to get grants, when they go out to commercialize their innovation, there is no shortage of both envious people and negative people. And the gravitational pull of that over time, if they don't build up that ambition muscle, it breaks them down because it takes a long time to succeed in healthcare. And what I've noticed is that that muscle, that ambition can dim. if you don't start and continually cultivate and surround yourself with other ambitious people who believe that the impossible is possible. Do you see that same thing in the Strategic Coach community? And I know topically in healthcare, it's harder than any other industry, but I just was interested in how you think about it in your community.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, there's a set of earlier concept in Coach which makes it possible for Strategic Coach entrepreneurs not to give in to envy. And one of them is Unique Ability, that there's no use comparing yourself with someone else because what you want to do is, where are you unique? And there's a million different ways that you can be unique. You know, for example, some people are great innovators, but they have the ability to put together a great innovative team, you know, of innovators. So first of all, I think entrepreneurism gives you an enormous amount more flexibility and possibility than if you work in a job where you're employed by someone else. And then it becomes very highly political because you don't know why someone gets promoted ahead of you, you don't know why new opportunities are given to someone else and not to you, and you're comparing yourself. So it's the act of comparing yourself to other people based on what you can see without any internal understanding of the other person. That is the root cause, I think, of all envy.

So I read a big book, very thick book, about five years ago—German scholar, dead, so he had died about 15, 20 years ago, and the book had been translated into English. There's 24 chapters on envy. The name of the book was Envy. And he just goes through human history, literature, politics, culture, everything, and he just shows how envy has always played almost a constant part in civilization. It's always been there. Shakespeare has it all over the place. The Bible, the Torah has envy. Cain is envious of Abel. He kills Abel. Joseph's brothers are envious of Joseph, because his father gave him a coat of multicolors, and they made it seem as if Joseph had been killed by an animal, but they got rid of Joseph as a source. So it doesn't matter what culture you're in, envy always plays a really big part, and it's a big part of psychology, the early roots of psychology. Everybody talks about envy until 1850, and no more talk about envy. So, you go to any psychological book today, and you look up envy, they say jealousy, but it's not jealousy, it's a totally different emotion. It is a totally negative emotion, it has no positive aspects whatsoever. So he says, very, very interesting. He said, if you look at it disappearing in 1850, because socialism became a major force, he says socialism is institutionalized envy. What do socialists want? They want really wealthy, successful people not to have what they have.

Steven Krein: That's the whole narrative.

Dan Sullivan: So you were talking about the new mayor of New York, who's a total socialist communist, if he actually tells it. And who supported him? It was college students who've gotten their future. They studied all their life to qualify to get into college. A lot of them are in debt in some way or another. And the job market has been cut off for them. And they're very, very envious of the students who came before them who just moved right from, a lot of them, you know, undergrad, but mostly graduate school, and they went right into a big investment bank. They went into a big, you know, law firm. You know, had to work their ass off, but they had a foot in. And that's been cut off. And AI is cutting off all entry-level jobs for highly educated, white-collar workers. And if you look at who supported Mamdani, and what do they go to? They go to extreme socialism to make things even, you know, because it's built on envy more. They don't see the house in the future, they don't see the big income in the future, they don't see the marriage in the future, anything. Now, if they talked about envy, it would probably be a more fruitful discussion.

Steven Krein: So without veering into politics and staying on entrepreneurship, now that you've elevated envy into the conversation is the opposite of ambition. People can work on being more ambitious, can cultivate ambition. Do you avoid people who are envious? How do you either neutralize it, is it just don't? By the way, I think about entrepreneurs, we were talking about this as it relates to selling out in the market. A lot of start-ups have to fundraise or get grants. And so you're bringing in people to your cap table, to your board, to your advisor group to help you. How do you think about curating? Let's talk about curating the people around you when you find there are envious people or that envy is pulling you down, a lot of innovation is stifled by envious people out there or organizations. How do you think about that? Or how do you think entrepreneurs should think about that?

Dan Sullivan: Well, you know, I live in a world that's been created over the last 36 years, basically. I mean, since we created the Program. And we've created levels of the Program. And one of the things that, you know, we're taking a look at is, how can we get more and more entrepreneurs into the future whose whole central motivation—I want to be around people where I can talk really about my biggest goals and I can talk about my biggest successes and not feel any pressure coming from them at all. And we can see it from Signature to the 10x level to Free Zone. Once you get to Free Zone, there's almost no envy. People are just very deeply interested in your success. They're very interested, not only in your success, but when you have a failure, what do you do with the failure? How do you use the failure as a really interesting learning experience? And then you recalibrate, you redirect, and you're off and running. And more and more, we've noticed the comments coming back to our team and to the coaches, the other coaches who coach the workshops, people say, you know what I love about Coach? I can be unambiguously ambitious and everybody loves it.

Steven Krein: Yeah. Yeah. You're not told to be less ambitious. You're not told that other people are doing it. And you're not given all the reasons why it can't work. Usually you're writing down more ideas than you can even execute on. You know, it was going back and just thinking about the parallel with StartUp Health and that the ideas of breakthrough health innovation is upending a lot of the flow of the way the money operates in healthcare. So if you're talking to an insurance company, you're talking to a pharma company, you're talking to providers, everybody's worried about disrupting the way the money flows. And it's interesting how, I would say, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed that came into this industry 20-plus years ago amazed that the rejection of ambitious, innovative solutions that could prevent, manage, cure diseases, and how many stories you hear about things getting either shelved, shut down, or not given any energy or oxygen because it disrupts where the money flows, so they don't wanna see anything succeed. So there is a lot of envy that pops up when people try to innovate.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, can I ask a question about it? Is the envy on the part of people in the industry who are entrepreneurs or people who are?

Steven Krein: Oh, no. They're not entrepreneurs, but they have control of money. They're not entrepreneurs, they sit in very powerful positions.

Dan Sullivan: They have the ability to say no.

Steven Krein: Yeah, well, it's funny because I was just watching this a great documentary I started watching on Netflix about Daniel Ek from Spotify. I'm three episodes in and he's pushing on, you know, the music industry and everybody that was pushing on the music industry. Pirate Bay, I think, was the other organization at the time, which was a very loose group of hackers that were just trying to kill the industry where nobody wins. Here comes along Daniel Ek, who realizes if we can pay the artists and make it easier for people to stream legally, everybody can win. But there's a shift in episode three where the CEO of Sony, I think it's Sweden, finally gets it because he is not letting entrepreneurs or any of the entrepreneurial thinkers in to exist, and they're trying to sue them and they're trying to do all this stuff. But then there's a flip where he realizes instead of being envious, let's join them. You know, you kind of see that obviously dramatized in a movie, but I think is the same thing. The industry is rejecting the innovators. They're in very powerful positions at the payers, the providers, the pharma and government in the way things flow. Nobody wants to see real innovation in so many areas because it disrupts the way the money flows.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it was a very interesting book. It was written in the 1960s by a writer, Thomas Kuhn, K-U-H-N, and it was called The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. You'll relate to this because he was asked, you know, when there's breakthroughs in a scientific field, when there's a breakthrough, all of a sudden you get a lot of breakthroughs. He said, what is your understanding of how these breakthroughs actually happen? He said, if you go back a year, two years, three years, four years, a lot of older scientists died. And they controlled promotion. They controlled funding. They controlled publication, which is very, very important in the scientific field. Do your papers get published? And he says, I think this is true of the scientific industry, but I think it's also true of every other industry, that people will get to a certain control factor. They're not creative, but they're controllers. And only their friends get the opportunities. Some new person coming along with a bright idea, he threatens everybody's pensions. He threatens what we achieved.

Steven Krein: So it doesn't allow the normal creative destruction cycle to take place.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, they try to stop it for a while. You know, and of course, ultimately, things, well, not everywhere in the world, but I think in the United States, that the founders, you know, I wrote a book previous to the Ambition book that was called The Bill of Rights Economy. And I just took the 10 First Amendments, and it's remarkable how supportive they are of entrepreneurs. And I said, yeah, but the founders, if you look at how they made a living, they were mostly entrepreneurial because there weren't corporations. Government hadn't formed enough yet that it could be in control. Plus, you had an unlimited geographic country. You had an unlimited demographic country. And I think that America had about 250 years when it could just be a wide open. But the moment it gets organized and the moment regulation comes in, then you start seeing that it's not everywhere in the country, that if you're an innovator, you don't have an opportunity here. Texas is a hotspot right now, but California isn't anymore. It's very hard to be an innovator in California because sooner or later, the controllers can control you.

Steven Krein: Yeah, yeah. Well, it's a unique moment in time once again with AI and too much of a topic to bring up to go deep on right now. But I think the shift that I'm seeing around businesses being created now with fewer people, better tools, and the tools seem to be designed for entrepreneurial thinkers. And I'm really wondering how much cooperation is going to be needed in the next decade and how much teamwork is going to be needed with industry as it relates to some of the unlocking of or democratization of solutions that can be brought to market by smaller teams that can pinpoint the weak spots and the problems and succeed. So the ambition-envy paradox is an interesting one to explore. I think it is at the core of what entrepreneurs are up against, I know, in healthcare as an industry. I wonder what the solution could be to arming a generation of entrepreneurs with that information and those skills and that ability.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, I think the first one is, as an entrepreneur, start using the tools for your own breakthroughs. I think that's really the key. You know, with Strategic Coach, I've sort of, you know, in a certain sense, I've created a culture where nobody tries to stop my innovations.

Steven Krein: So just worry about your own culture, your own company.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, because you create, you know, one thing that I really believe that Dunbar's Law really, really works, that even if you took someone like Elon Musk, you say, you know, he can deal with anyone he wants to. He seems to know how to bypass a lot of opposition. You know, he's kind of learned how to bypass. I mean, they're, you know, I mean, we're out of the billions category when you get to Elon Musk and people at the top of the industry. They're starting to talk about trillions, you know. Trillions is a big number, you know. And anyway, they're talking about maybe Tesla should just pay him a trillion dollars, you know. And I said, well, he owns Tesla.

Steven Krein: Yeah, I guess he can. By the way, you could do a whole episode on that, the ambition versus envy and that whole situation.

Dan Sullivan: But really his community is probably around 15, 20 people. You know, he's surrounded himself, you know, and you see it in the political world. You see it in, Taylor Swift is a really interesting example. You know, it's not my music and it's …

Steven Krein: You're not a Swifty, Dan?

Dan Sullivan: No, I'm not.

Steven Krein: I have three daughters, so I have no …

Dan Sullivan: I'm a Nat King Cole guy. I love Pandora because she can just design your whole music culture and it just surrounds you. But it's very, very interesting that she and the team that she put together, because she obviously has a great team from childhood that's really understood her abilities and have created a structure and infrastructure where she can just do what she wants.

Steven Krein: She's as optimized as you can get, yeah.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, but my feeling is, does Taylor Swift at 35 have a bigger future than she has in the past?

Steven Krein: Because who she attracted were more or less her age, and now they're … I'll tell you something, very interesting topic, because I was just talking about that. I have three girls, my wife, we have a Taylor Swift house, but you can imagine the music that just came out. So the kids memorize it. It's a whole culture, but it's defying age. She's navigating her life. And unlike Billy Joel, which I just watched that documentary where he just stopped making music for a long time and writing, she is continually, you know, she had her Eras tour, which was, you know, she just did her 12th album. So every year or so, whatever's going on in her life becomes, you know, what she writes about. Now she's engaged, getting married. She'll have kids and things like that. You'll see, I think, her transition really well. She seems to get the idea of waving goodbye to the past and creating the future. And she talks a lot about creating a future bigger than our past. I do know that, again, just using that Billy Joel analogy, you know, he stopped writing music, new music, and all of the stuff he plays is now from, you know, 20 plus years ago. If she continues reinventing herself and reinventing what her music's about, I think it transcends the generations. I mean, she seems to get the formula. And interestingly enough, I think her teamwork that you described, her Unique Ability team gets it too.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, in the performing arts. She's really the great example of doing it. It may take a completely different form, you know, at a certain point. She's probably not going to do a tour like that again. I mean, once you've done that tour, there isn't a bigger tour that you can get to. We were in Buenos Aires not this year, but last year, because Buenos Aires, she had four concerts in a week. It was sold out six months beforehand. As a matter of fact, the stadium, it was an open-air stadium where she was doing it. And people had been camped out for six weeks before the concert. I mean, there was like a whole market there. I mean, she had it everywhere she went. Yeah. I mean, she was an economic force. Of course, she wanted her to come to your city because she came to Toronto and it closed. Not that the traffic was any good before him, but the traffic was horrific.

Steven Krein: Business went up. Yeah. Everyone's businesses went up.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And that's, you know, if you're going to be that type of person, you have to bear that in mind, that you're the buyer for a long period of time. Everybody wants you to come to their city, which is really, really good. You're the one who can walk. They can't walk.

Steven Krein: You're the buyer, not the seller. Dan, wrapping up this episode, what's your biggest insight from this conversation around ambition?

Dan Sullivan: Well, it really reminded me to take a look at who are the non-creative controllers that can stop creativity. I mean, Joe Polish has a close relationship with Robert Kennedy. When he was just running as a Democrat, and of course, they cut off the possibility of him primarying, you know, nobody could primary Biden, you know, they just cut it off that there would be no primary. And so finally he had to go independent, you know, but he wasn't going to get, I mean, he might get an electoral vote. And I was telling people, I said, you have to understand the two-party system. You have to understand the Electoral College. He could get 30% of the vote and not get one electoral vote. I mean, that's the way the system, it's a very stabilizing system that they've created. There can only be two big parties. If one of them fails, there will be another one that replaces it, but there won't be three parties. There will just be two parties. There are people who gain status without having talent and their motivation becomes to prevent talent from replacing their status. It's an interesting thing, but that's envy. That's envy.

Steven Krein: It's envy. Well, I look forward to your probably next tool that touches on ambition.

Dan Sullivan: It's fun because it's an unexamined part of life. I love unexamined parts of life that you can create patents out of.

Steven Krein: Dan, always enjoy our conversation. Great seeing you.

Dan Sullivan: Thank you, Steve.

Related Content

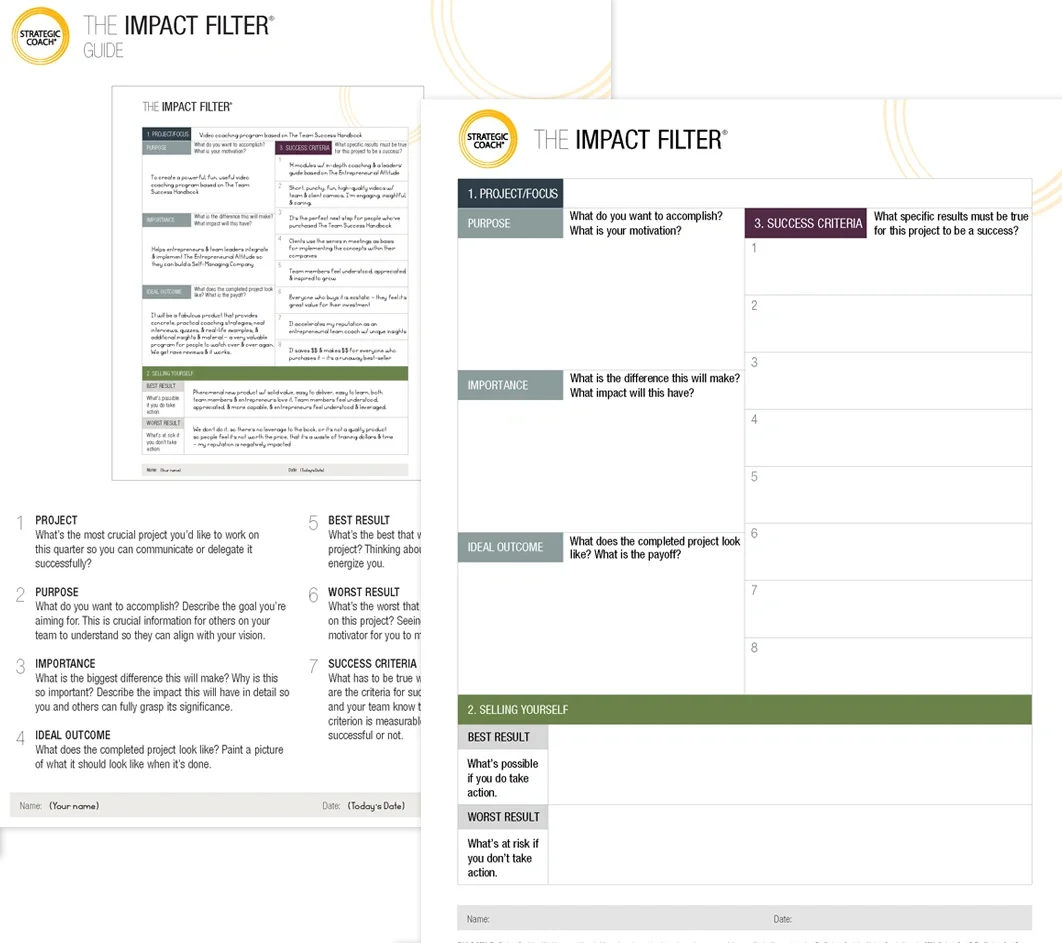

The Impact Filter®

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.